Climate is changing. And nowhere is it more evident than near Earth's poles. Life that has adapted to these extreme regions – including sea ice-dependent species from tiny algae to huge polar bears – is being impacted. Salinity is a "key ingredient" for high-latitude ocean ecological communities. Why? It affects seawater density which, in turn, influences the movement of water, heat, and carbon.

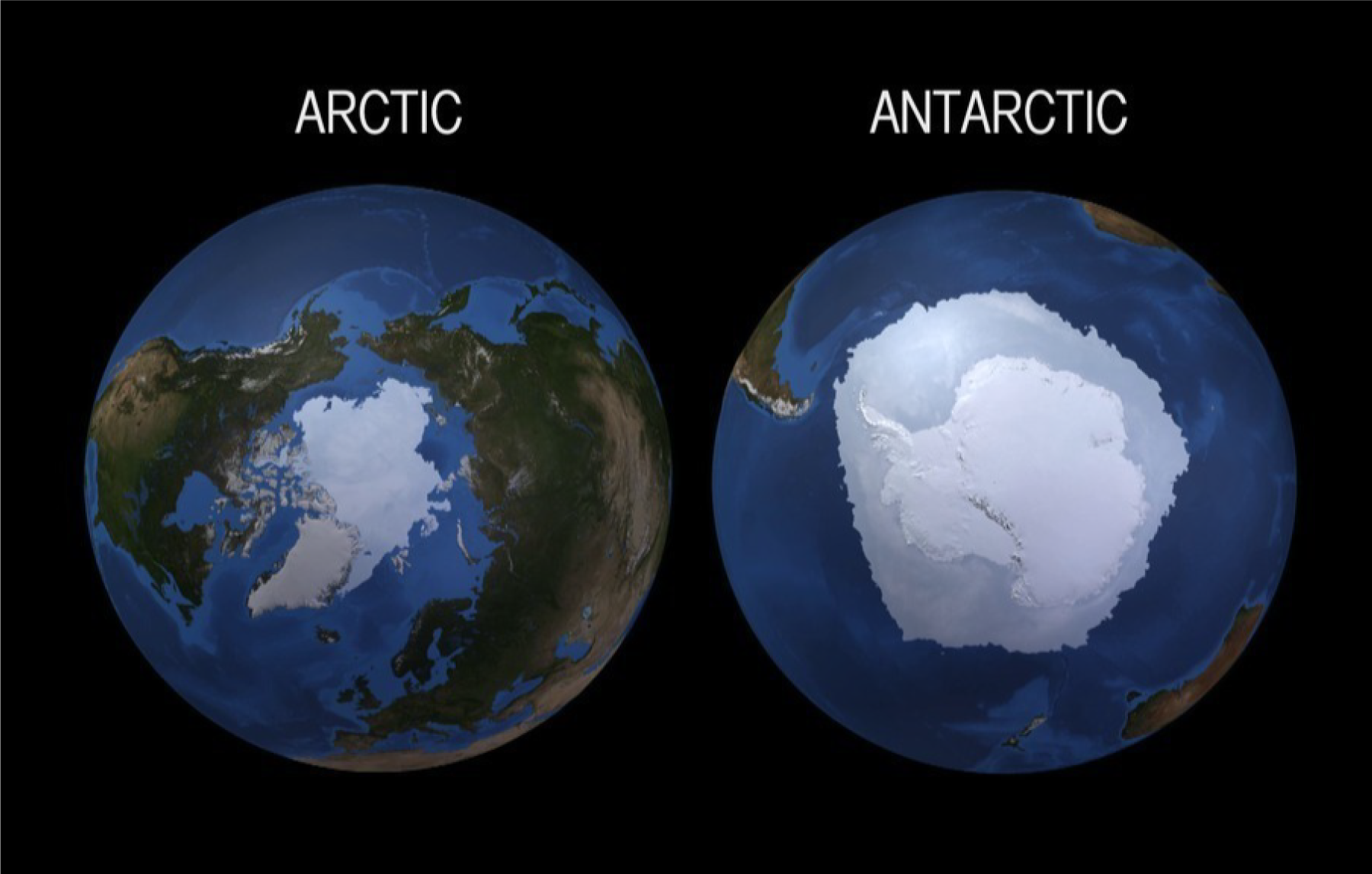

A basin surrounded by land, the Arctic Ocean has a cap of frozen seawater (a.k.a. "sea ice") that waxes and wanes. For years, satellites have tracked sea ice growth each winter and the dramatic extent of sea ice melt each summer. In the Arctic Ocean, thermohaline (i.e., temperature- and salt-controlled) layering is vital to maintaining the cold, relatively fresh surface waters that support diverse ecosystems. However, measuring cold-water salinity from space is challenging.

Antarctica is a large continent surrounded by the Southern Ocean. Because of this geography, sea ice has more room to expand in the winter. So, sea ice – along with other ice that originated on land such as icebergs – can move into warmer latitudes and melt. Being the only place where our seas circle Earth without being slowed down by land, the Southern Ocean is prone to very high winds. Along with cold temperatures, a wind-roughened sea surface hampers the accurate measurement of salinity from satellite.

Use the tool below – based on studies by Lind et al. (2018) and Haumann et al. (2016) – to investigate the characteristics of salinity in the Arctic and Antarctic. Use the buttons to toggle between locations.

Changes in Arctic freshwater distribution impacts ocean circulation, climate, and life. This study explores the use of satellite-derived sea surface salinity (SSS) as a proxy for Arctic freshwater changes. It builds on previous work that used satellite‐derived sea surface height (SSH) and ocean bottom pressure (OBP) to infer depth‐integrated freshwater content changes. This proof‐of‐concept study analyzes the output of an ocean‐ice state estimation product, finding that SSS variations are coherent with SSH-minus-OBP across much of the Arctic basin.

Fournier, S., Lee, T., Wang, X., Armitage, T., Wang, O., Fukumori, I., and Kwok, R. (2020). Read the full paper.

Hudson Bay, the largest semi-inland sea in the Northern Hemisphere, is completely covered by ice and snow in winter. About six months each year, however, satellite remote sensing of sea surface salinity (SSS) can be retrieved over open water. This provides some insight into freshwater cycles in the Arctic Ocean where SSS data are scarce. The study found that the main source of the year-to-year SSS variability in Hudson Bay is sea ice melting. The freshwater contribution from surface forcing precipitation minus evaporation (P-E) is smaller in magnitude but lasts through the entire open water season. River discharge is comparable with P-E in magnitude but peaks before ice melt.

Tang, W., Yueh, S., Yang, D., Mcleod, E., Fore, A., Hayashi, A., Olmedo, E., Martínez, J., and Gabarró, C. (2020). Read the full paper.

This study presents the first systematic analysis of six commonly used sea surface salinity (SSS) products from NASA and the European Space Agency in terms of their consistency among one another and with in-situ data. When averaged over the Arctic Ocean, the products show excellent consistency in capturing seasonal and year-to-year variations. The products also consistently identify regions with strong SSS variability over time. However, many challenges still exist in retrieving Arctic SSS because brightness temperature (TB) has lower sensitivity in colder waters at the frequency employed by today's SSS satellites (i.e., L-band). View the One-pager. Read about an evaluation and intercomparison of SMOS, Aquarius, and SMAP SSS products in our Research Insights.

Fournier, S., Lee, T., Tang, W., Steele, M., and Olmedo, E. (2019). Read the full paper.