Approximately one quarter of the carbon dioxide (CO2) that we emit into the atmosphere is absorbed by the ocean. CO2 uptake can decrease seawater pH and the concentration of carbonate ions, a process known as ocean acidification (OA).

Four key parameters are necessary to assess OA: pH, total alkalinity (TA), dissolved inorganic carbon, and the partial pressure of CO2. All but pH have some dependency on salinity. Scientists can use any two of these parameters to evaluate changes in the ocean's carbonate system.

Today’s efforts to monitor OA chiefly rely on in situ data, which provide sparse geographic coverage. Satellites, however, have the potential to provide consistent, global data for OA studies. For example, recent studies show that global TA can be assessed using satellite-derived salinity data.

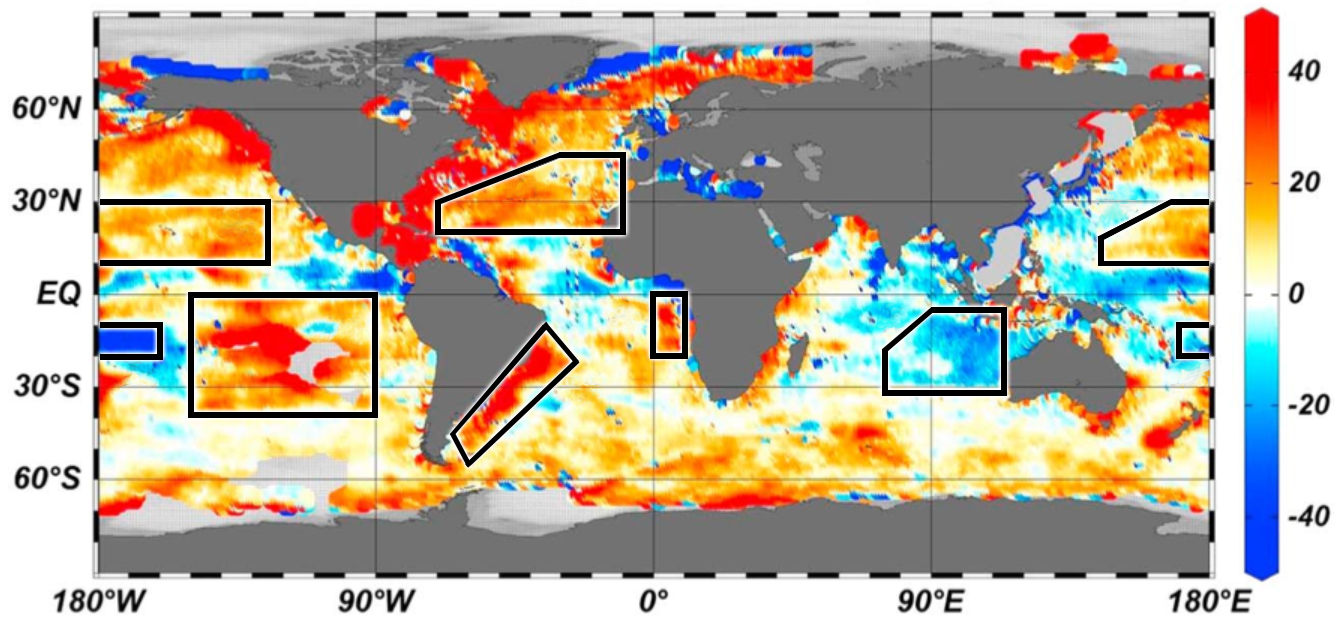

Research shows that OA - and changes in TA - are not occurring uniformly across the ocean. Some regions are acidifying faster than others (Land et al., 2016). Use the tool below – based on a study by Fine et al. (2016) - to see the difference between annual averaged satellite‐derived TA concentrations in 2014 and TA concentrations from the World Ocean Database (1975–1984). This includes increases in subtropical regions, consistent with large-scale trends in Earth's water cycle. Boxes are regions where there have been significant changes in TA. Single-headed arrows signify TA changes of 20-50 μmol/kg. Double-headed arrows signify TA changes greater than 50 μmol/kg.

Routine measurements from space can provide quasi-synoptic, reproducible data for investigating processes on global scales; they may also be the most efficient way to monitor the ocean surface. As the carbon cycle is dominantly controlled by the balance between the biological and solubility carbon pumps, innovative methods to exploit existing satellite sea surface temperature and ocean color, and new satellite sea surface salinity measurements, are needed and will enable frequent assessment of ocean acidification parameters over large spatial scales.

Land, P.E., Shutler, J.D., Findlay, H.S., Girard-Ardhuin, F., Sabia, R., Reul, N., Piolle, J.-F., Chapron, B., Quilfen, Y., Salisbury, J., Vandemark, D., Bellerby, R., and Bhadury, P. (2015). Read the full paper.

This work demonstrates how large‐scale Aquarius satellite salinity data have provided an unprecedented opportunity when combined with total alkalinity (TA) equations as a function of salinity and temperature to examine global changes in the CO2 system.

Fine, R.A., Willey, D.A., and Millero, F.J. (2016). Read the full paper.

Space-based observations offer unique capabilities for studying spatial and temporal dynamics of the upper ocean inorganic carbon cycle and, in turn, supporting research tied to ocean acidification (OA). Satellite sensors measuring sea surface temperature, color, salinity, wind, waves, currents, and sea level enable a fuller understanding of a range of physical, chemical, and biological phenomena that drive regional OA dynamics as well as the potentially varied impacts of carbon cycle change on a broad range of ecosystems. Here, we update and expand on previous work that addresses the benefits of space-based assets for OA and carbonate system studies.

Salisbury, J., Vandemark, D., Jönsson, B., Balch, W., Chakraborty, S., Lohrenz, S., Chapron, B., Hales, B., Mannino, A., Mathis, J.T., Reul, N., Signorini, S.R., Wanninkhof, R., and Yates, K.Y. (2015). Read the full paper.